Introduction

- Atrial fibrillation is a common supraventricular tachycardia

- Incidence in Canada is up to 4.5% per year, with lifetime risk estimated at 25% among those older than 40 years of age

- Evaluation of the patient involves:

- Determining the underlying cause of atrial fibrillation and modifying risk factors

- Rate- or rhythm-control strategy

- Stroke prevention (role of anticoagulation)

Definitions

- Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia characterized by uncoordinated atrial activation with consequent deterioration of atrial mechanical function.

- On an electrocardiogram (ECG), AF is described as the replacement of consistent P waves with rapid oscillations or fibrillatory waves that vary in size, shape, and timing, and are associated with an irregular, frequently rapid ventricular response.

- Irregularly irregular rhythm

- Clinical classifications:

- Paroxysmal AF: Continuous for >30 seconds and <7 days

- Persistent AF: Continuous for > 7 days and < 1 year

- Long-standing persistent AF: > 1 year and pursuing rhythm control

- Permanent AF: Decision made to no longer pursue sinus rhythm restoration

- Patient may have both paroxysmal and persistent episodes and should be classified based on dominant episodes

- Valvular AF: Atrial fibrillation in the presence of any mechanical heart valve, or in the presence of moderate to severe mitral stenosis (rheumatic or non-rheumatic)

- Important implications for anticoagulation choice

Differential Diagnosis

- The differential diagnosis for tachycardia is broad. Tachycardia is usually classified based on morphology of the QRS (wide complex or narrow complex), rhythm, and presence or absence of p-waves.

- Please refer to the following sites for further details:

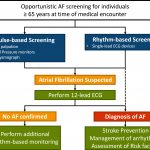

Screening

- Opportunistic screening is recommended for individuals over 65

- Generally done using pulse palpation as part of standard physical exam but can also use rhythm based screening with single-lead ECG

- If concern, obtain 12-lead ECG and if non-diagnostic but clinical suspicion remains high consider rhythm-based monitoring.

- Post stroke: 24 hours of rhythm based monitoring recommended and longer if AF still suspected

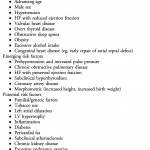

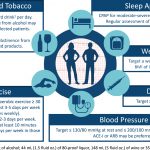

Risk Factors

- Pathophysiology of AF is a complex and evolving field

- There are many cardiac and non-cardiac conditions that increase risk and are associated with AF (seen in table)

- Recommended to systematically approach modifiable risk factors and treat using guideline directed management

Initial Workup

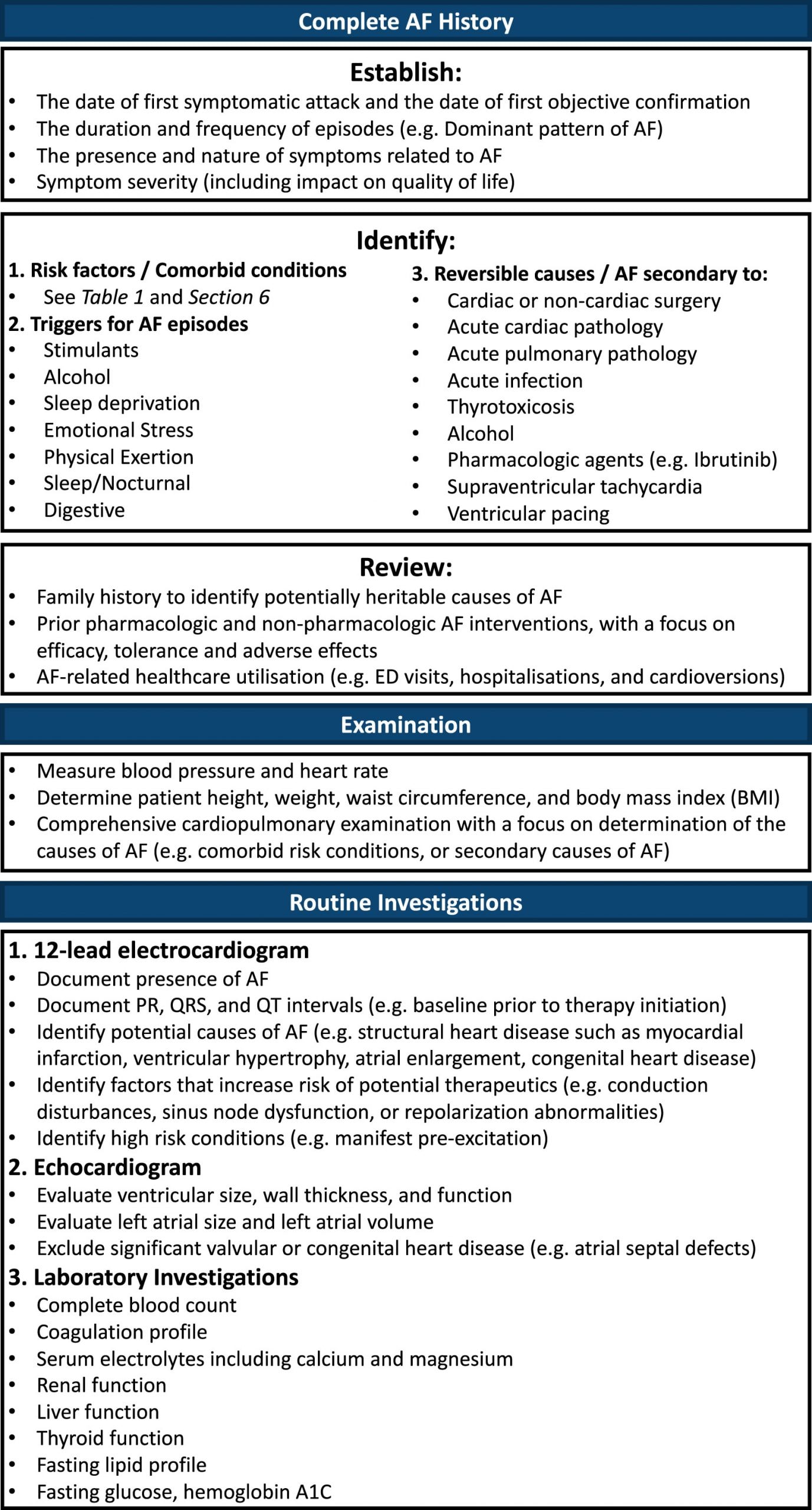

History

- Identify risk factors

- Obtain thorough history on duration and frequency of attacks and if currently in atrial fibrillation, when episode started

- Presence, nature and severity of symptoms (impact on QoL using CCS SAF scale)

- Ie. palpitations, shortness of breath, chest pain, syncope or presyncope (conversion pauses), and focal neurologic deficit (embolic stroke)

- Precipitating factors and preventable causes (ie. caffeine or hyperthyroidism)

- Bleeding profile

- Previous therapies (ie. rate control, rhythm control, cardioversions, and/or ablations)

Routine Investigations

- 12-lead ECG

- Presence of AF, baseline intervals (PR, QRS, QT), signs of structural heart disease (ie. LVH, atrial enlargement)

- Echocardiogram

- LV size, wall thickness, and function

- Left atrial size and volume

- Labs

- CBC, coagulation profile, electrolytes (including calcium and magnesium), renal function, liver function, thyroid function, fasting lipid profile, fasting glucose + hemoglobin A1C

- Further investigations depending on history

- Ie. if concern for sleep apnea then sleep study or if

Physical Exam

- Assess for AF risk factors and secondary causes of AF

- Vitals (BP and HR), height, weight and BMI

- Atrial Fibrillation

- Irregular jugular venous pulsations (JVP)

- Irregularly irregular rhythm detected by palpation of pulse or auscultation

- Heart sounds heard during auscultation may include

- Variable intensity of first heart sound (S1)

- Absence of a fourth heart sound (S4) heard previously during sinus rhythm

- Comprehensive cardiac exam including looking for heart failure signs (elevated JVP, edema, lung crackles)

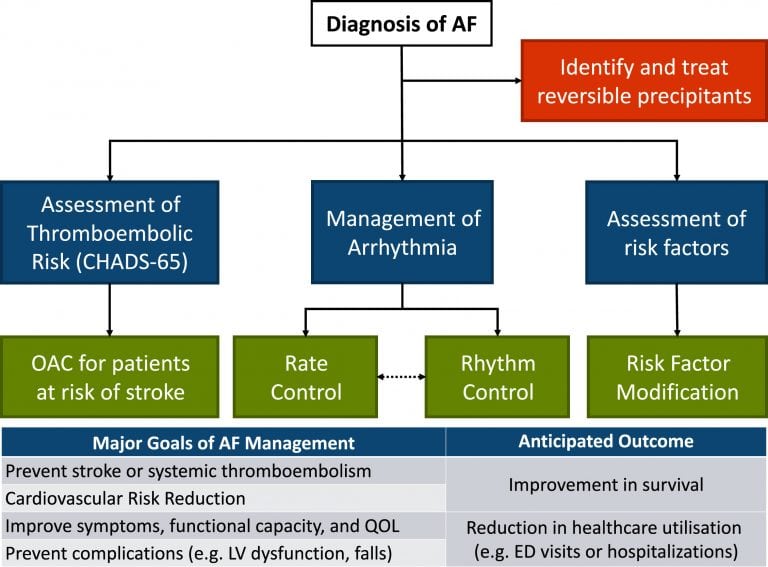

Overall Management

Stroke Prevention

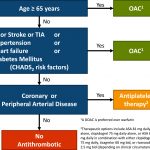

CHADS-65

- All patients should have yearly assessment of their AF stroke risk

- Canadian guidelines recommend following the CHADS-65 algorithm for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Essentially all patients with either one CHADS risk factor or over 65 should be offered anticoagulation

- Anticoagulation discussion should be individualized to each patient balancing their stroke and bleeding risk

Anticoagulant Selection

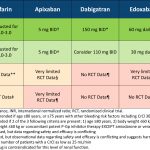

- DOACs (apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran) are recommended over warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Refer to table for dosing of DOACs (adjust for renal function and apixaban for weight/age/creatinine)

- Some experts recommend apixaban 2.5mg BID and Edoxaban 30mg OD for CrCl 15-29

- Warfarin is indicated for valvular atrial fibrillation (mechanical valve and moderate-severe mitral stenosis)

Acute Management

- If atrial fibrillation is due to a reversible or secondary cause, focus should be on treating the primary issue

- Ie. if a septic patient develops atrial fibrillation, resuscitating the patient should be the primary goal

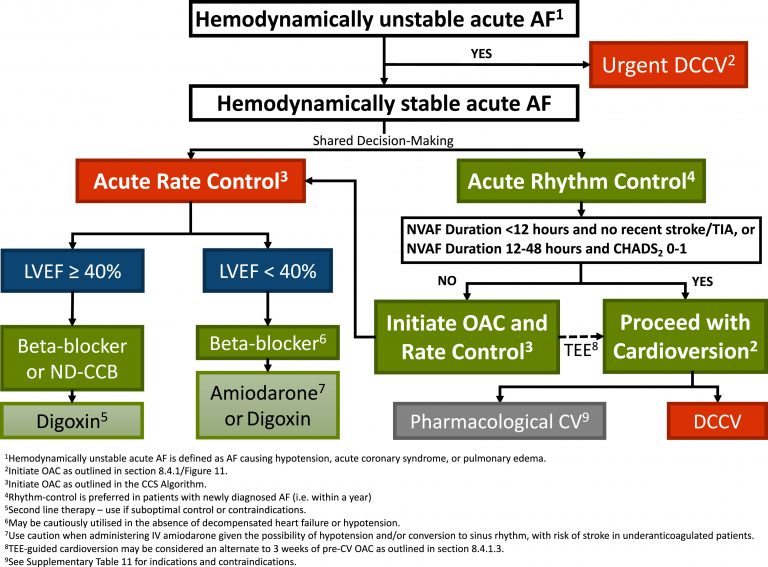

- Patients that are hemodynamically unstable should be managed as per ACLS and undergo electrical cardioversion (see cardioversion algorithm below)

- In stable patients, shared decision making to decide on acute rate vs rhythm control

- Recent-onset atrial fibrillation, guidelines recommend rhythm control strategy as recent evidence suggests reduced cardiovascular death and rate of stroke (EAST-AFNET 4)

- Established atrial fibrillation there is no difference in outcomes between rate and rhythm control (AFFIRM)

- Rate control can be done with beta blockers and/or calcium channel blockers (if EF>40%) and remember to start oral meds as soon as possible after IV

- Acute Rate Control Agents and Acute Rhythm Control Agents

Cardioversion

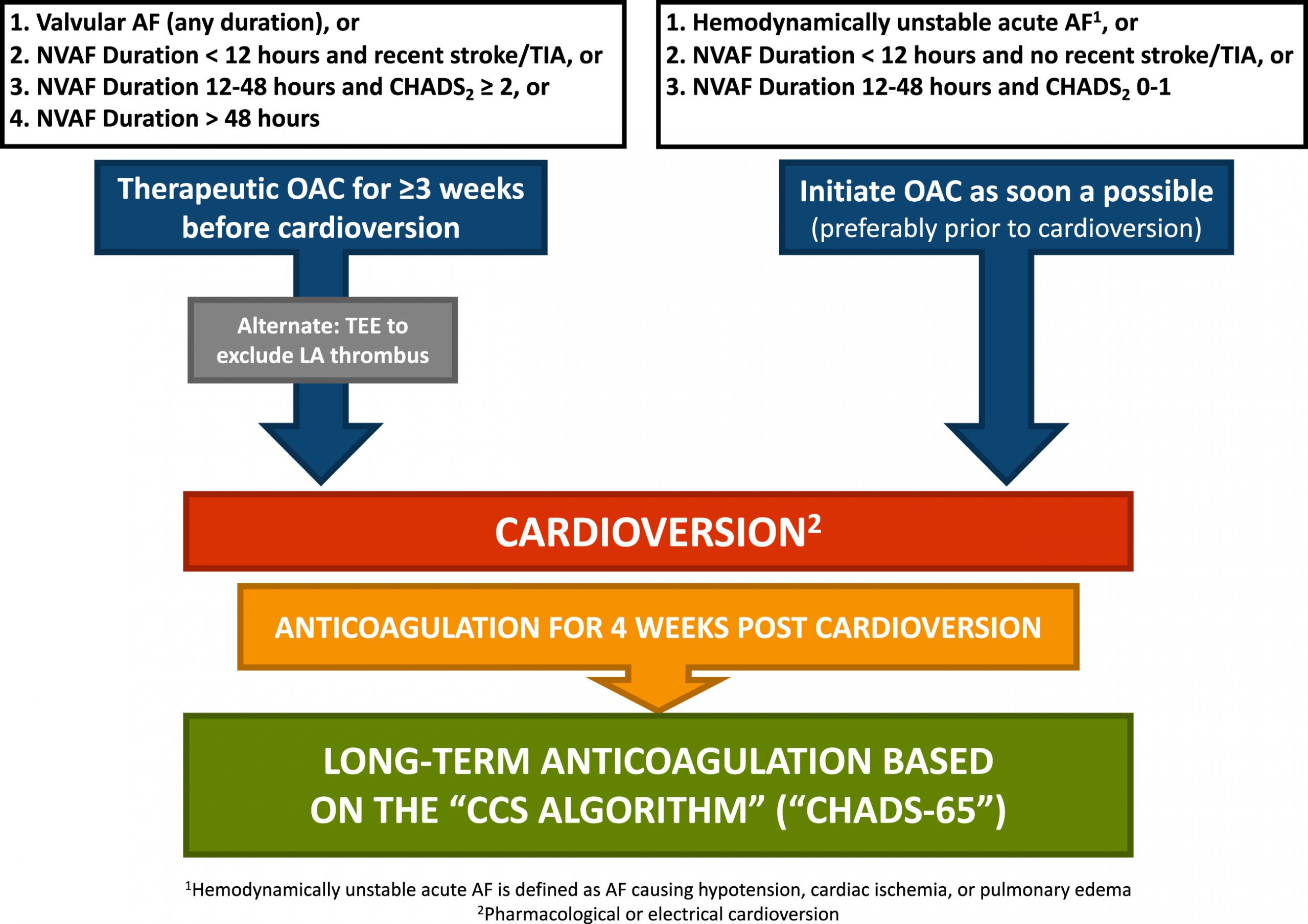

- Note specific duration criteria for whether cardioversion can be safely done vs needing either 3 weeks of anticoagulation vs TEE

- Anticoagulation should be started as soon as possible (ideally before cardioversion)

- Note: CHADS 0 patients under 65 also require anticoagulation for 4 weeks post cardioversion and everyone else long term

- Recommend using max dose joules (ie. 150-200 J biphasic) to avoid repeated shocks

- Pad placement (AL vs AP) does not seem to influence success)

- Obese patients may require applying force over pads using paddles to improve success

Long Term Arrhythmia Management

Approach

- As above, patients with recent onset of atrial fibrillation, rhythm control strategy is a reasonable choice to prevent negative cardiovascular and stroke outcomes (especially in higher risk patients, see EAST-AFNET 4 study above)

- Otherwise using both rhythm and rate control have similar outcomes and decision should be individualized to the patient.

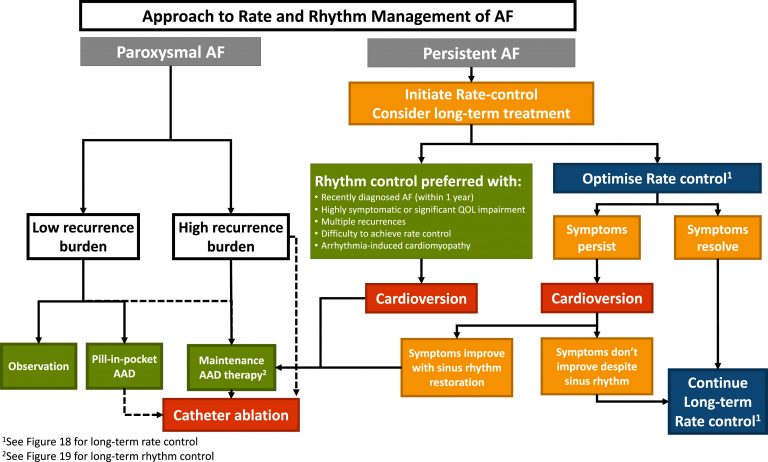

- CCS provides a framework below for how to choose strategy

Rate-Control

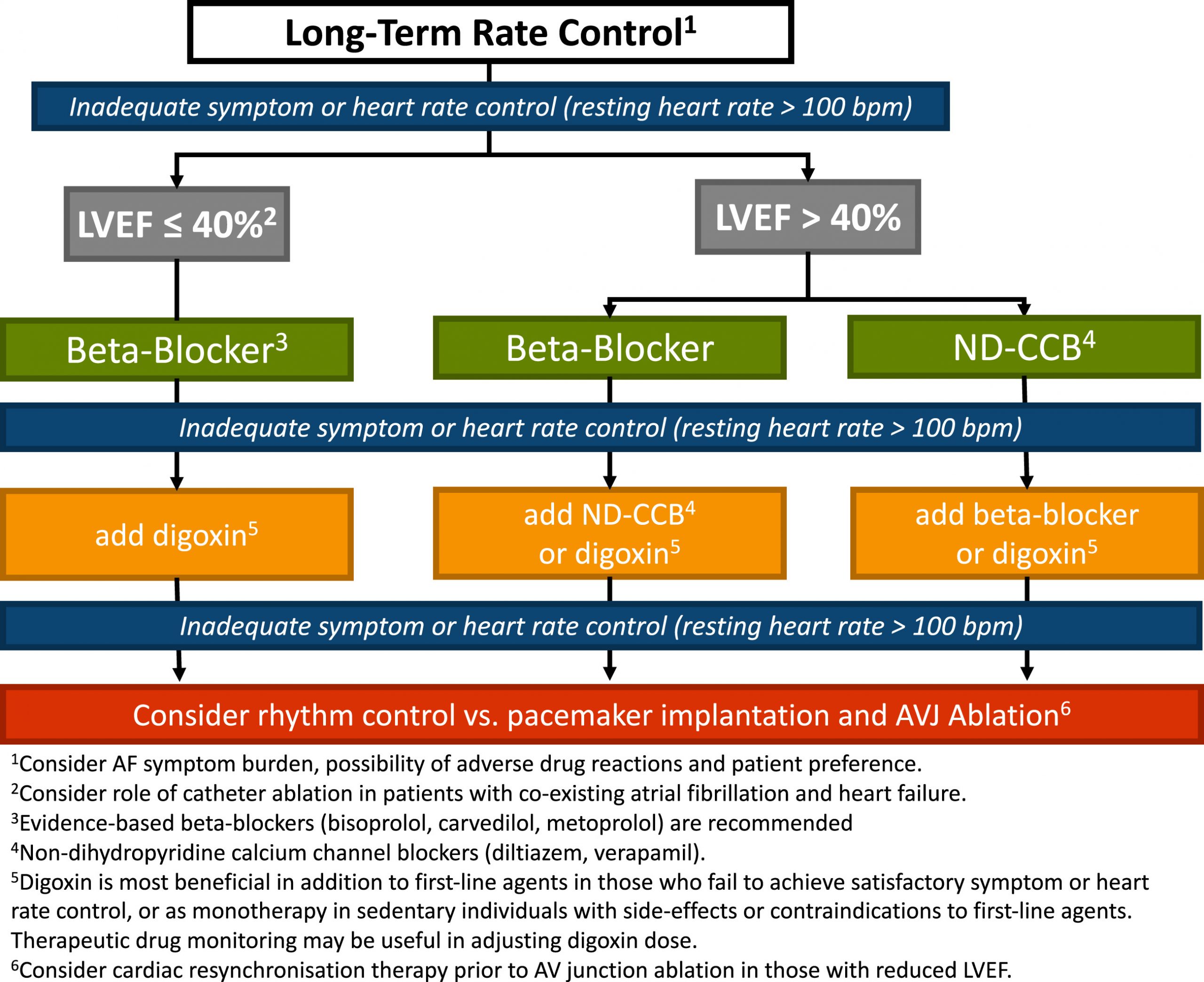

- Goal is to minimize effect on quality of life

- Aim for a resting heart rate of < 100 beats per minute in permanent atrial fibrillation

- RACE II: Among patients with permanent atrial fibrillation, lenient rate-control (HR < 110 bpm) is as effective as strict rate-control (HR < 80 bpm) in preventing cardiovascular events

- Initial therapy should be beta blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers

- Beta blockers preferred in patients with myocardial infarction or systolic dysfunction

- Digoxin can be used as monotherapy in older or sedentary patients, unable to tolerate first-line medications, or as an add on if rate control target not achieved

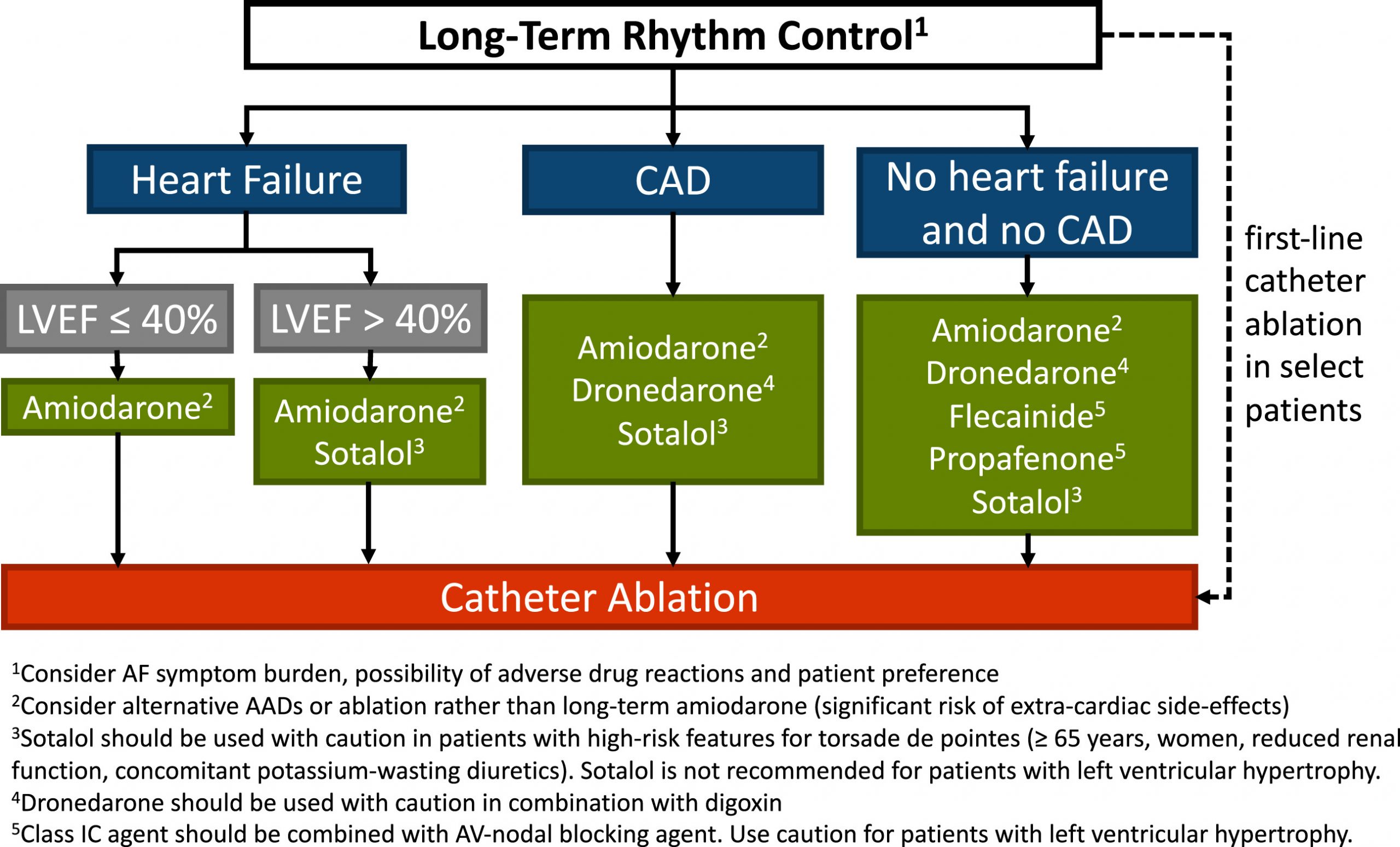

Rhythm-control

- Recommended in patients who are symptomatic despite rate control, in whom rate control is thought to unlikely control symptoms, or recent onset atrial fibrillation

- Rhythm control agent should be chosen based on whether they have heart failure or CAD

- Pill-in-pocket strategy can be used for patients who have infrequent symptoms

Amiodarone

- Acutely, IV amiodarone acts as a beta-blocker and can help rate control atrial fibrillation

- Chronically, amiodarone is the most effective medications for atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation. Patients require a total of 10 grams to saturate their tissues such that their serum levels remain high. At that point, the half-life becomes very long and it becomes an effective anti-arrhythmic medication.

- Drug monitoring:

- TSH ad LFTs (baseline and q6 months)

- Chest Xray and ECG (baseline and q1year)

- PFTs (baseline and again if symptoms)

- Ophthalmic exam (if symptoms)

Catheter Ablation:

- Can be used in patients who are highly symptomatic despite adequate rhythm-control trial (drug-refractory) and in whom rhythm control is desired

- Can be utilized in select individuals are first line therapy (e.g. paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that is highly symptomatic) or individuals with pre-excitation atrial fibrillation with an accessory pathway

- Can be utilized as first line therapy or as a reasonable alternative to pharmacologic rhythm- or rate-control therapy patients with symptomatic typical atrial flutter

- Since catheter ablation is an invasive procedure, risks and benefit must be balanced

Management - Special Scenarios

Anticoagulation/Antithrombotic Post PCI

- Risks and benefits of anti-thrombotic therapy need to be balanced carefully

- A list of factors that may help with balancing risk and benefit of anti-platelet and anticoagulation therapy

- Duration of triple therapy can be decided after a discussion with the Interventional Cardiologist, who is familiar with patient’s coronary anatomy and thrombotic risk.

- Generally, the duration of triple therapy is 1-3 weeks, which was the timeframe used in clinical studies.

- Clinicians managing cardiac patients must be familiar with OAC management after PCI. Please carefully review the graphic titled “CCS 2020 – Management of antithrombotic and anticoagulant therapy post ACS/PCI”

- NOTE: that “Dual Therapy” and “Triple Therapy” have different OAC dosing. This was established in clinical trials.

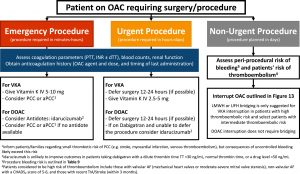

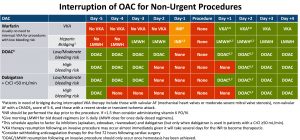

Peri-Operative Anticoagulation Management

- The decision to continue or stop anticoagulation should be based on risk of bleeding during procedure

- See algorithm for specific management of warfarin vs DOAC and bridging schedule

- Note: DOACs do not require bridging due to short half life

Managing Bleeding on Anticoagulation

- Management of bleeding on anticoagulation depends on the severity of bleeding and type of anticoagulant.

- Note: for emergencies warfarin has multiple reversal agents, dabigatran can be reversed with idarucizumab and the anti-factor Xa (apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban) drugs can be reversed with andexanet alfa

End-stage Renal Disease

- CKD Stage 3 (GFR >30) and Stage 4 (GFR 15-29): anticoagulation is recommended as per CCS CHADS65 algorithm

- CKD Stage 5 (GFR <15 or dialysis): guidelines recommend not routinely not performing anticoagulation but this is an area of ongoing debate

Liver Disease

- Anticoagulation is not recommended for patients with Child-Pugh grade C or significant coagulopathy

Left Atrial Appendage Closure

- Area of ongoing discussion but considered in patients with absolute contraindication to anticoagulant and are at risk of stroke

- Can be done surgically or percutaenous

Further Reading

Authors

- Authors: Dimitar Saveski (MD, Internal Medicine Resident), Atul Jaidka (MD, FRCPC, Cardiology Resident)

- Staff Reviewer: pending (MD, FRCPC[Cardiology])

- Copy Editor: Perri Deacon (medical student)

- Last Updated: April 12, 2021

- Comments or questions please email feedback@cardioguide.ca